Whether or not one has read Marcel Proust’s works, you might be familiar with his “madeleine,” the cookie that initiates his 1913 novel The Remembrance of Things Past: Swann’s Way by transporting him through time and memory. Jen Grazza, as if to signal how books, as objects, can be similarly evocative, depicts the first six pages in three paintings (2011). The paintings are striking upon first glance, with their prestidiginous skill and academic precision (the type-face text of whole pages re-created down to the very serif), and it quickly becomes apparent that their virtuosity belies a painterly, if somewhat conservative, sensibility.

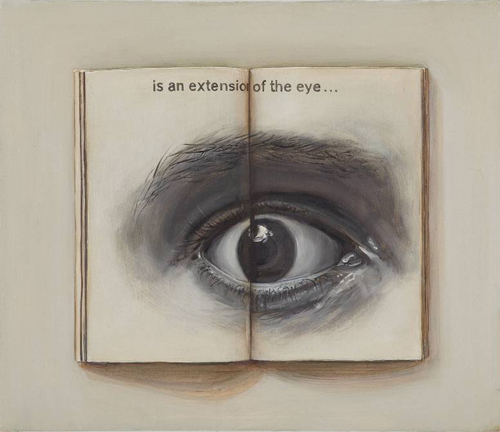

Most of the works in Grazza’s exhibition “The Words (Le Mots)” feature books, in fact—either the cover or pages opened to text or an illustration. Each one, centered and parallel to the picture plane, is surrounded with hazy old-master-esque backgrounds of layered glazes of alternating warm and cool colors. These abstract yet individuated backgrounds function as a signal that Grazza’s careful paintings of her singular subjects are more akin to portraiture than still life painting. Recalling the oft-quoted line by Gilbert Highet (used frequently on Barnes & Noble paraphernalia): “These are not lumps of lifeless paper, but minds alive upon the shelves!”

Throughout the exhibition, Grazza displays an astonishing knack for duplicating style, including imitations of the affably bland graphic design of old Penguin paperbacks, as in Civilization (2012), loopy middle-brow Modernism as seen in Le Planetarium (2011), the fine curlicues of various logos and publisher’s imprints, and a reproduction of a Rothko in Le Ravissement (2012). The trompe l’oeil accuracy is impressive and yet, fortunately tends to fall short of pastiche. Grazza is always duly conscious her sources as fastidiously copied images and attributes of objects. They convey not just the original printed materials, but also the ravages of time: the dusty yellow pages, faded colors on the covers, and the wear, tear, creases, scuffs-marks, and folds which provide evidence the books were read and loved. This attention to the book as object also becomes a metaphor for the individual relationships that readers have to books as texts – how everyone’s experience of the same book is, nonetheless, unique.

One might say Grazza is attempting to reverse the effects described by Walter Benjamin in his essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”: to re-invest the mechanically reproduced object with the “aura” of a specifically personal one. The play of light and shade on the edges of pages and brown leather covers is treated with a variety of coloristic flourishes typically reserved for the human figure. These ostensibly drab elements are modulated with several nameless, fleshy shades of beige, grey, tan, ochre and mauve (as well as a few rogue notes of teal or light violet high-lights). This gives them a certain oily corporeality that recalls, perhaps ironically, De Kooning’s famous assertion, “Flesh is what oil paint was made for,” as well as the not-quite-dissimilarly biblical phrase, “And the Word became flesh.”